Vautherin rail fastening

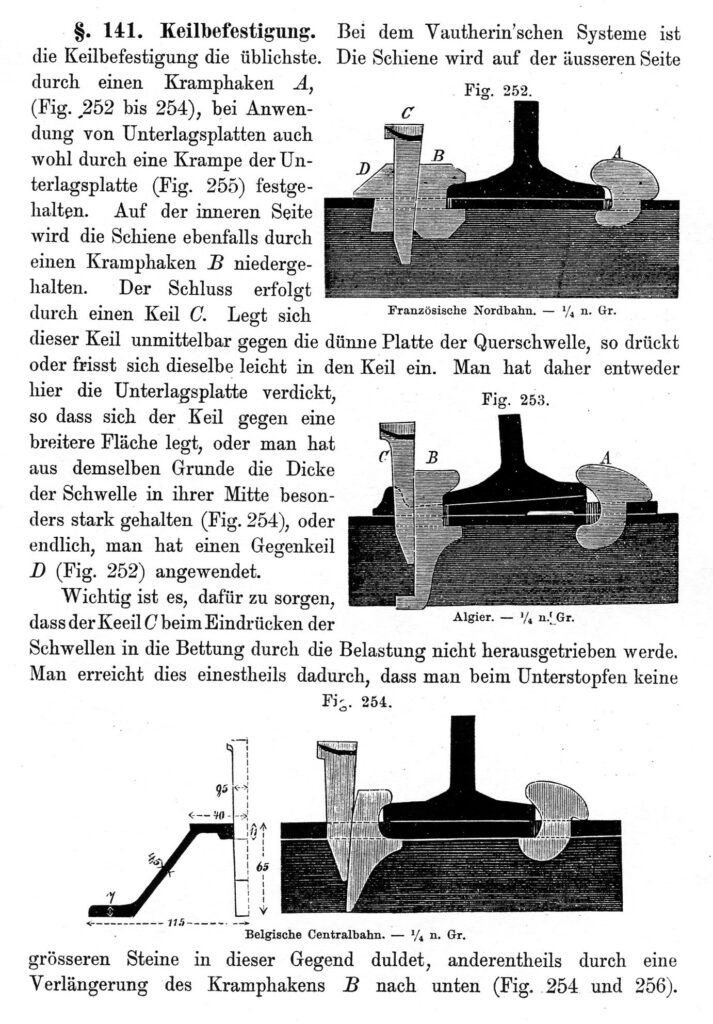

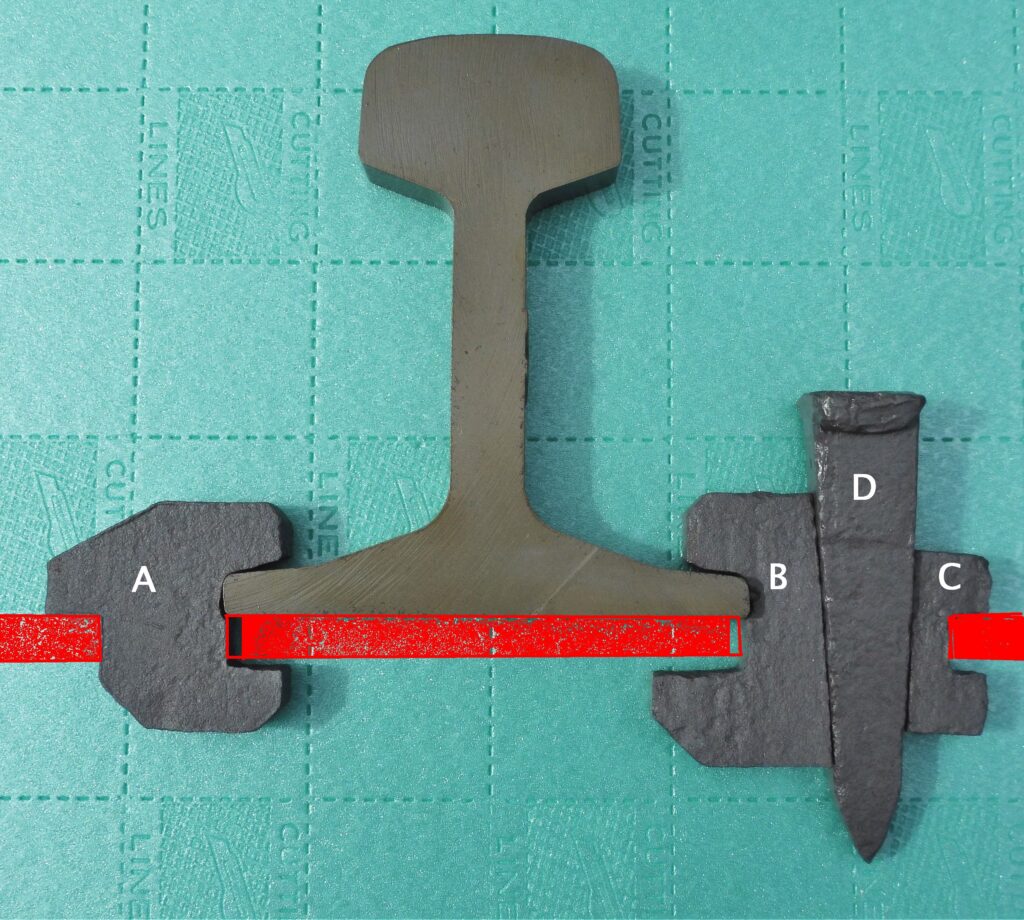

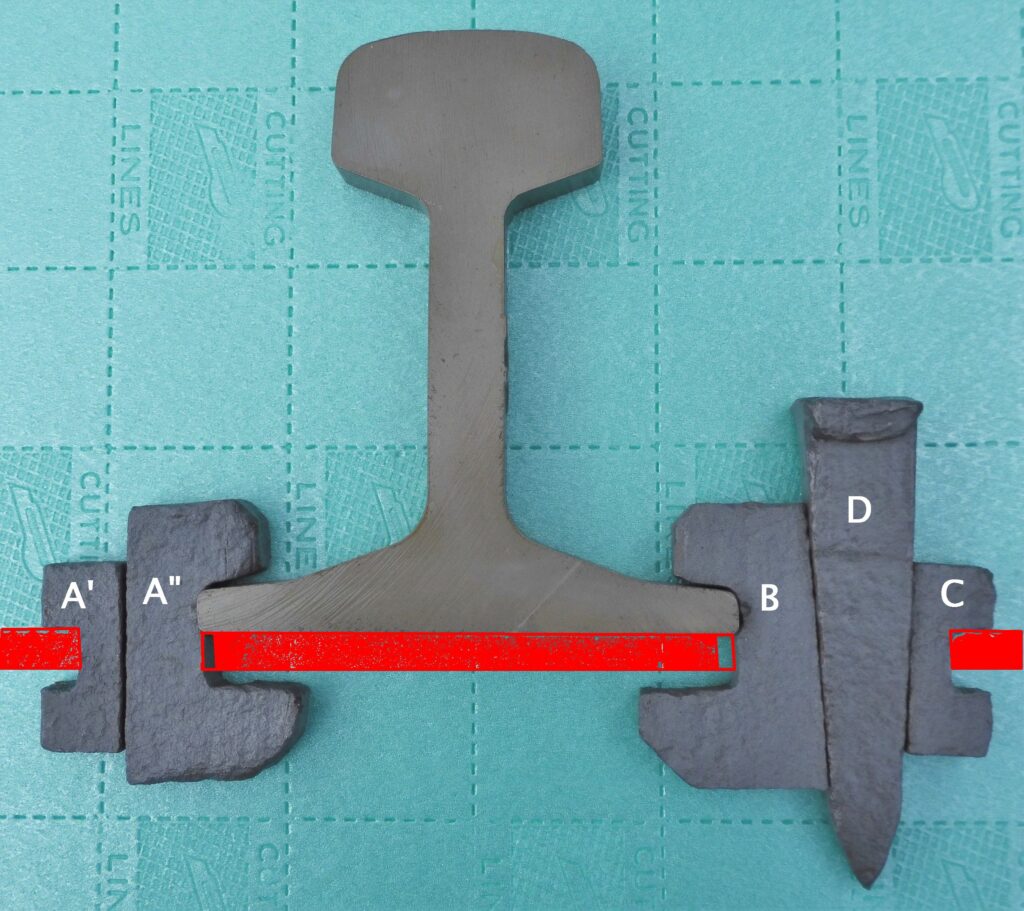

From 1862, iron sleepers came into use with the aim of achieving a longer lifespan than with wooden ones. For flat bottom rails on those sleepers, of course, different rail attachments had to be developed than were used on the wooden ones. As usual, many different systems emerged, some quite complicated and others simple. In a single system, wooden blocks were mounted on the sleeper, in which the common collar screws could still be used. Vautherin’s fastening was one of the simple systems. It is described in Die Eisenbahn-Oberbau by Dr E.Winkler from 1875 and in other manuals as well. Two rectangular holes must be punched in the top surface of the sleeper, in one of which a hook is placed that holds the rail foot, in the other two U-shaped components with a steel wedge in between. By hitting the wedge with a hammer, the rail is completely locked. In some situations a slightly different method was followed, but always with that steel wedge. The rail head and rail foot widths, together with the desired track width, determine the distance at which the holes must be punched. It is clear that changes in those head and foot widths when using a rail profile other than the original would require either an adjustment of the hooks used or other sleepers. Changing the holes or making new ones is not an option in the iron or (later) steel sleepers. Contrary to the advantage of simplicity, there was the major disadvantage that the punched rectangular holes gave rise to crazing from their corners. The system has been in use in a number of countries, is now hardly visible, but in some railway museums.

In 2007 Olaf Mensch noticed the Vautherin fastenings in a siding at Freudenstadt Hbf (Baden-Württemberg, Germany) and in 2011 also near the Rübelandbahn in the Harz (Germany). By a very lucky coincidence it was recently known that the Freudenstadt track would be broken up. Due to the care of some concerned DB employees, the Vautherin parts ended up in the collection. Many of the wedges used were found to have the number 2 in the head, which presupposes that keys with a different width or a different shape and therefore with a different number in the head were originally used for the same system. Information on such details has not yet surfaced.